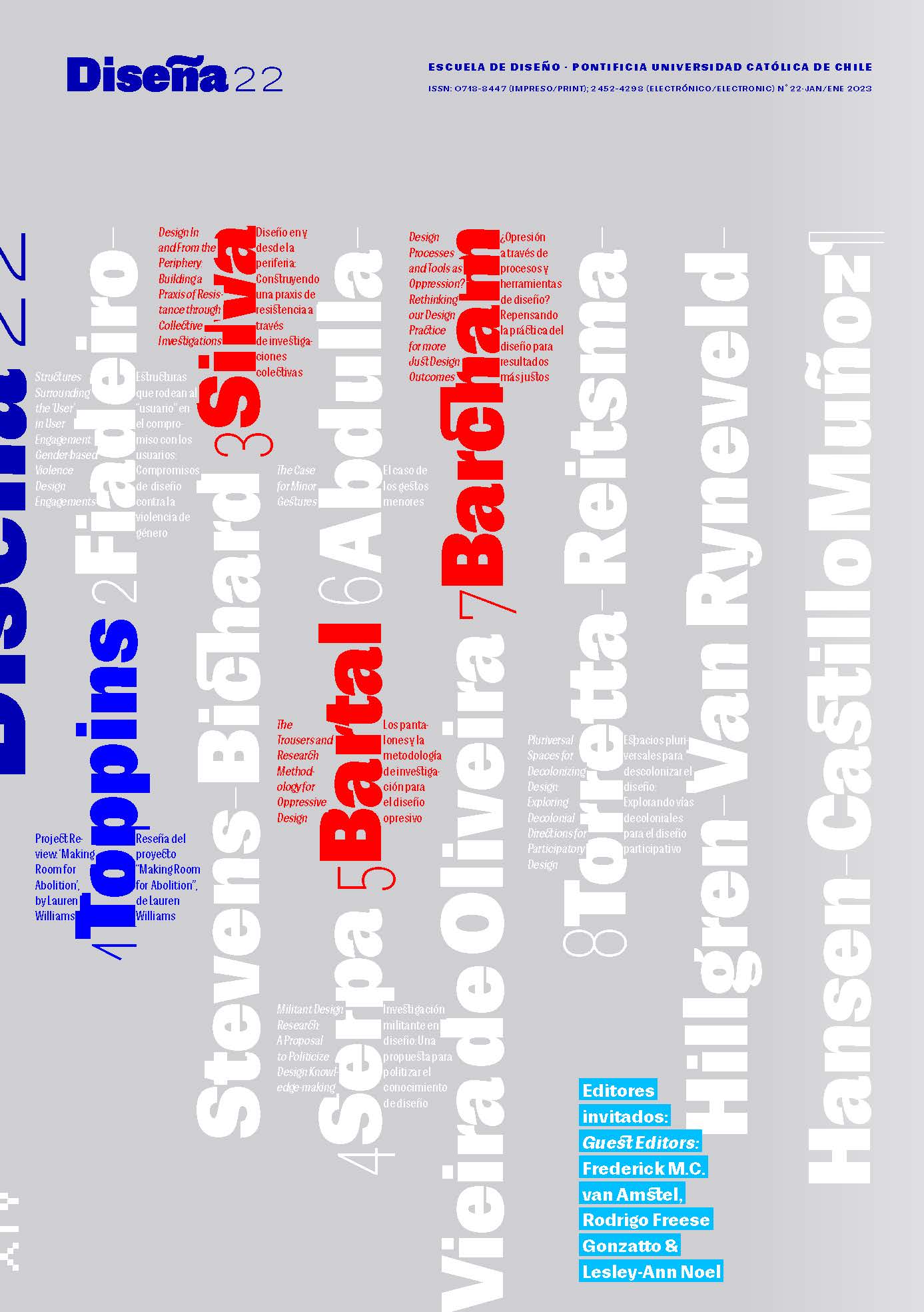

Design Processes and Tools as Oppression? Rethinking our Design Practice for more Just Design Outcomes

Main Article Content

Abstract

Our design processes and tools matter, as our design is always shaped by the processes and tools that we use. Context necessarily shapes the content of our design processes and tools. But, without paying attention to the content emerging from that context, the use of these tools and processes may become oppressive. In the wake of colonialism, the un-reflexive use of design tools and processes underpinned by Western conceptual ideas and schema can lead to oppression for design with non- Western or Indigenous peoples. Even tools and processes designed with a supposedly liberatory intent, such as promoting democratic practice or equality, can lead to oppression in their un-reflexive use. Looking at two experiences from my design practice with my own hapū (clan), this article explores the ways in which ideas of democratic participation and equality raised in these two design spaces could function in an oppressive way to cause a form of violence against our traditional lifeworld. This article proposes some ways in which this aspect of design might be modified to help lead to more just design outcomes, through a more reflective and intentional approach when choosing and applying the design tools and processes we use in our design practice.

Downloads

Article Details

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International license.

COPYRIGHT NOTICE

All contents of this electronic edition are distributed under the Creative Commons license of "Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 Internacional" (CC-BY-SA). Any total or partial reproduction of the material must mention its origin.

The rights of the published images belong to their authors, who grant to Diseña the license for its use. The management of the permits and the authorization of the publication of the images (or of any material) that contains copyright and its consequent rights of reproduction in this publication is the sole responsibility of the authors of the articles.

References

Barcham, M. (2021). Towards a Radically Inclusive Design – Indigenous Story-telling as Codesign Methodology. CoDesign, (advance online publication). https://doi.org/10.1080/15710882.2021.1982989

Barcham, M. (2022). Weaving Together a Decolonial Imaginary Through Design for Effective River Management: Pluriversal Ontological Design in Practice. Design Issues, 38(1), 5–16. https://doi.org/10.1162/desi_a_00666

Bishop, M. (2021). ‘Don’t Tell Me What to Do’ Encountering Colonialism in the Academy and Pushing Back with Indigenous Autoethnography. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 34(5), 367–378. https://doi.org/10.1080/09518398.2020.1761475

Blessett, B., Dodge, J., Edmond, B., Goerdel, H. T., Gooden, S. T., Headley, A. M., Riccucci, N. M., & Williams, B. N. (2019). Social Equity in Public Administration: A Call to Action. Perspectives on Public Management and Governance, 2(4), 283–299. https://doi.org/10.1093/ppmgov/gvz016

Corntassel, J. (2012). Re-envisioning Resurgence: Indigenous Pathways to Decolonization and Sustainable Self-determination. Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society, 1(1), Article 1.

Costanza-Chock, S. (2020). Design Justice: Community-Led Practices to Build the Worlds We Need. MIT Press.

Coulthard, G. S. (2014). Red Skin, White Masks: Rejecting the Colonial Politics of Recognition. University of Minnesota Press.

Escobar, A. (2020). Pluriversal Politics: The Real and the Possible (D. Frye, Trans.). Duke University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv11315v0

Fanon, F. (1961). The Wretched of the Earth. Grove Press.

Freire, P. (2014). Pedagogy of the Oppressed (30th-anniversary ed.). Bloomsbury.

Gutiérrez Borrero, A. (2015). Resurgimientos: Sures como diseños y diseños otros. Nómadas, (43), 113–129.

Haraway, D. (1988). Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective. Feminist Studies, 14(3), 575–599.

Ingold, T. (2013). Making: Anthropology, Archaeology, Art and Architecture. Routledge.

Kolodny, N. (2014). Rule Over None I: What Justifies Democracy? Philosophy & Public Affairs, 42(3), 195–229. https://doi.org/10.1111/papa.12035

Kovach, M. (2009). Indigenous Methodologies: Characteristics, Conversations, and Contexts. University of Toronto Press.

Liao, S., & Carbonell, V. (2022). Materialized Oppression in Medical Tools and Technologies. The American Journal of Bioethics, (advance online publication), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/15265161.2022.2044543

Liao, S., & Huebner, B. (2021). Oppressive Things. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 103(1), 92–113. https://doi.org/10.1111/phpr.12701

Lorde, A. (1983). The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House. In C. Moraga & G. Anzaldúa (Eds.), This Bridge Called My Back, Fourth Edition: Writings by Radical Women of Color (pp. 94–101). Kitchen Table Press.

Mcguire and Makea v Hastings District Council and the Maori Land Court of New Zealand. (2002). Australian Indigenous Law Reporter, 7(1), 53–60.

Minow, M. (2021). Equality vs Equity. American Journal of Law and Equality, 1, 167–193. https://doi.org/10.1162/ajle_a_00019

Mutu, M. (2015). Māori Issues. The Contemporary Pacific, 27(1), 273–281. https://doi.org/10.1353/cp.2015.0015

Quijano, A. (1991). Colonialidad y Modernidad/Racionalidad. Perú Indígena, 13(29), 11–20.

Santos, B. de S. (2018). The End of the Cognitive Empire: The Coming of Age of Epistemologies of the South. Duke University Press. https://doi.org/10.1215/9781478002000

Saunders, B. (2010). Why Majority Rule Cannot Be Based only on Procedural Equality. Ratio Juris, 23(1), 113–122. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9337.2009.00446.x

Sheehan, N. W. (2011). Indigenous Knowledge and Respectful Design: An Evidence-Based Approach. Design Issues, 27(4), 68–80. https://doi.org/10.1162/DESI_a_00106

Smith, L. T. (2012). Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples. Zed.

Suchman, L. (2002). Located Accountabilities in Technology Production. Scandinavian Journal of Information Systems, 14(2), 91–105.

Taboada, M. B., Rojas-Lizana, S., Dutra, L. X. C., & Levu, A. V. M. (2020). Decolonial Design in Practice: Designing Meaningful and Transformative Science Communications for Navakavu, Fiji. Design and Culture, 12(2), 141–164. https://doi.org/10.1080/17547075.2020.1724479

Tlostanova, M. (2017). On Decolonizing Design. Design Philosophy Papers, 15(1), 51–61. https://doi.org/10.1080/14487136.2017.1301017

van Amstel, F. M. C., Noel, L.-A., & Gonzatto, R. F. (2022). Design, Oppression, and Liberation. Diseña, (21), Intro. https://doi.org/10.7764/disena.21.Intro

Walker, S., Evans, M., Cassidy, T., Jung, J., & Twigger Holroyd, A. (2018). Design Roots: Culturally Significant Designs, Products, and Practices. Bloomsbury.

Willis, A.-M. (2006). Ontological Designing: Laying the Ground. Design Philosophy Papers Collection, 3, 80–98.

Winograd, T., & Flores, F. (1986). Understanding Computers and Cognition: A New Foundation for Design. Ablex.

Winschiers-Theophilus, H., Chivuno-Kuria, S., Kapuire, G. K., Bidwell, N. J., & Blake, E. (2010). Being Participated: A Community Approach. Proceedings of the 11th Biennial Participatory Design Conference, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1145/1900441.1900443